Ravens All-Time Top 5 QBs: Hometown Heroes & Workout Wonders

Lamar Jackson defies his doubters, Kyle Boller throws from his knees and Joe Flacco outlasts his hecklers.

Let’s hop in our time capsule and explore the first quarter of the 21st century together.

1. Lamar Jackson

I think wide receiver. Exceptional athlete. Exceptional ability to make you miss. Exceptional acceleration. Exceptional instincts with the ball in his hands, and that’s rare for a wide receiver: that’s A.B. [Antonio Brown] and who else? Name me another one who’s like that? Julio’s [Jones] not even like that. This guy is incredible in the open field and a great ability to separate. And again: short, and a little bit slight. And clearly, clearly not the thrower that the other guys are. His accuracy isn’t there. And so I would say: don’t wait to make that change. Don’t be like the kid from Ohio State [Terrelle Pryor, probably] and be 29 when you make that change. – Bill Polian, discussing what position Lamar Jackson should play in the NFL on Golic and Wingo, Feb 19, 2018.

It was a Chargers scout, he was the one who told me about it. Like, he was the first one to come to me about it, and I'm like, 'What?' He caught me off guard with it. I even made a face for him like, 'What?' I'm thinking he's trying to be funny, but he kept going with it, so it just became blown out of proportion.

He was like, 'Oh, Lamar, you're going to go out for some wide receiver routes?' I'm like, 'Nah, quarterback only.' So that made me not run the 40 and participate in all that other stuff.’ – Lamar Jackson, on the Combine rumor that he was asked to work out as a wide receiver, via John Breech of CBS Sports, June 2018.

We have covered 20 quarterbacks so far in the Top 5 QBs series. Lamar Jackson is our first black quarterback. (Tua Tagovailoa is Samoan.) In a way, we’re beginning the story of black quarterbacks in pro football at the end.

Black quarterbacks will be asked to change positions again in the future, just as some white quarterbacks are still asked to do, because that really is the best option for some of them. Racially-tinged opinions about quarterbacks, and everyone else, will remain with us for a long time. But no prospect of Jackson’s caliber will ever again be so casually, erroneously “othered.”

The athlete-playing-quarterback trope was in its death throes in the mid-2010s: everyone from Warren Moon through Donovan McNabb to Russell Wilson had been shoveling dirt on it for decades. While pure scramblers like Pryor (26 when he moved from quarterback to receiver) might still change positions, it became increasingly rare in the middle of the last decade for anyone with Jackson’s resume — a Heisman Trophy, two 3,500-plus yard collegiate passing seasons — to be branded as lacking the magical qualities required of an NFL quarterback.

Then came Colin Kaepernick.

The last eight years have been so speed-plotted that it’s easy to forget what a hornet’s nest Kaepernick kicked in 2016, which was also the most divisive presidential election year in living memory until the next two. Agreeing or disagreeing with Kaepernick’s stance – let’s stay on Ravens/Jackson topic in the comments, please – doesn’t change the fact that he kicked a hornet’s nest.

Publicly, the NFL plastered on a polite smile and tried to be all things to everyone when Kaepernick began protesting during the national anthem. Privately, the hivemind reconciled its implicit biases, its desire to win and the change in the political pressure system with the fact that Kaepernick was on the job market in 2017 by coming to the conclusion that Scrambling Quarterbacks Don’t Work in the NFL.

The rapid declines of Kaepernick and Robert Griffin were the hivemind’s cover for this absurd claim. They fed their most willing mouthpieces this hogwash, which was eagerly regurgitated. The league even made a golden idol out of Mike Glennon – the slowest, gawkiest quarterback they could pretend to really like – and made him the subject of deafening offseason buzz in 2017.

I’m not suggesting that anyone in the NFL consciously said, let’s shun black quarterbacks so the president doesn’t tweet about us. No one had to. Homogeneous groupthink is a powerful tool for conformity. Herds instinctively run from predators while remaining in a tight pack. Kaepernick wasn’t signed because scrambling quarterbacks are stinky-poo is a dumb, obvious, cowardly dodge. But if everyone sticks to the story …

Anyway, Jackson arrived on the draft scene while the NFL was still telling tall tales about Kaepernick and sociopolitical protest in sports remained newsworthy: Polian’s infamous Jackson take came just days after the Eagles made political activism a Super Bowl talking point. It also came at a time when grouchy old white guys felt extra-empowered to state things they long kept stifled. By the winter of 2018, Polian was hearing the same things I was hearing, off-the-record, from close-to-the-league sources: it’s not that we hate the social justice movement – heaven forbid – but our offensive coordinator just doesn’t like the read-option, blah-blah-blah. Polian was more predisposed than others to parrot the talking points without criticism.

The clapback against Polian, in particular, was overwhelming. It continues to this day, because the athlete-playing-quarterback dog whistle remains an open wound.

Ultimately, Jackson did not just prove his implicitly-biased critics wrong but made them look stupid. The distinction is critical: being wrong a lot comes with the job of being a scout, GM, coach or columnist. Being a moron too many times gets you fired.

Lamar Jackson, Part II

Jackson has now led the Ravens to a 2-4 postseason record. Here is an incomplete list of other notable quarterbacks who led their teams to exactly two career postseason victories as starters:

Ken Anderson: 2-4

George Blanda: 2-2

Blake Bortles: 2-1

John Brodie: 2-3

Daunte Culpepper 2-2

Jim Everett: 2-3

Rex Grossman: 2-2

Billy Kilmer: 2-5

Joe Namath: 2-1

Tony Romo: 2-4

Chad Pennington: 2-4

Dak Prescott: 2-5

Alex Smith: 2-5

Kordell Stewart: 2-2

Vinny Testaverde: 2-3

Richard Todd: 2-2

Michael Vick: 2-3

What a chaotic, fun and mostly-meaningless list! And yet, I think it illustrates … something.

Jackson is not often compared to Ken Anderson, but if you squint you can see similarities. Both had early peaks followed by several injury-marred years before reaching second peaks. Both played the quarterback position in a unique way for their eras and led the league a few times in emergent categories: efficiency rating for Anderson; quarterback rushing statistics for Jackson. Both kept crashing into brick walls in the playoffs. Anderson eventually took the Bengals to the Super Bowl, but his teams struggled in “big games” throughout the 70s.

As you might imagine, I am not much of a QB WINZ guy. Still, when evaluating and categorizing all-time greats, I want to see playoff victories and conference championship appearances. Several of the quarterbacks on the list above are precluded from Hall of Fame consideration or mention among the upper-echelon quarterbacks of their era precisely because they are on the list above. Jackson, of course, should move well beyond it in the next few years, as should Prescott, but there are no guarantees.

There’s a big difference between evaluating a quarterback’s worthiness to start on Sunday each week and his qualifications for entering a pantheon. Jackson can unequivocally be judged according to those higher standards now. I look forward to seeing him continue to meet them.

2. Joe Flacco

I attended a family graduation party for some of my high school students in July of 2009. Some fellow teachers and I were drinking beers with parents and less-recent graduates around the fire pit when the starting quarterback for the Ravens strolled into the back yard, flanked by his parents and several of his siblings. Joe Flacco grew up a few houses down the street and was tight with the guest-of-honor’s older brother.

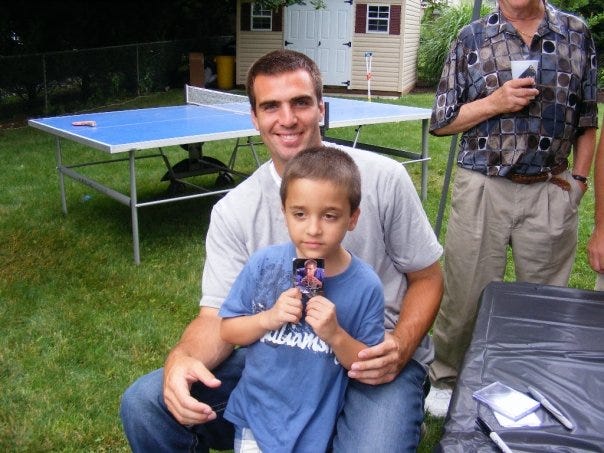

Joe tossed a nerf ball around. My son C.J. was six at the time, and he and another teacher’s son played a game in which they tried to “sack” Joe. He picked them up and held them upside down with his left arm and threw passes to other youngsters with his right. He stopped by the fire pit to chat about life in the NFL with his former teachers by twilight, then joined his brothers and their pals for ping-pong and horseshoes.

For those who don’t know my thrilling backstory: I was a math teacher from 1992 through 2011. Joe Flacco was in my calculus class at Audubon High School in the early 2000s. He grew up one town over from where I live. He still lives two towns and tax brackets up Kings Highway with his wife (same calculus class) and their oodles of children.

Joe was too tall for his body until his senior year of high school. Audubon ran a T-formation offense when he was an underclassman, which was understandable: the typical neighborhood quarterback in these parts cannot throw 50 yards down the sideline with accuracy. A new coach brought a spread offense when Flacco was a senior, but he couldn’t bring receivers taller than 5-foot-9 or faster than the typical gym-class hero.

Joe committed to Pitt, got stuck behind Tyler Palko and transferred to Delaware. I taught two of his brothers and his sister during that span. My writing career also began to take off. I was covering the draft for Deadspin (yes, I really am the Grim Reaper) when Joe was drafted. As I recall, I was invited to his draft party, though I did not attend.

I have never been comfortable speaking as a media member about my tangential relationship to the young Flacco. Mentioning it felt like jock sniffing. Not mentioning it felt coy.

Some folks really dug the “Flacco’s former teacher” angle early on. Peter King mentions it every single time he introduces me at a function. When Flacco took the Ravens on their Super Bowl run, my editors at Sports on Earth wanted me to tell my “Flacco story” and/or use local connections to gain access. I did what I had to do to appease my employer.

Whenever I wrote about Flacco, the story risked becoming “my” story, which is precisely what is happening as I type this. I don’t mind writing about myself as a lifelong Philly sports fan, child of the 1980s, tipsy wallflower or face of a dying industry. I despise writing about myself as a writer who is supposed to be writing about something or someone else. “Look at me!” blogging was popular 15-20 years ago, I enjoyed success because of it, and I hate it. I came to this career after spending years learning that students only ask their teachers about themselves because they find the class boring. If I am telling the story of the NFL in a compelling way, you should not care what I drink or what’s on my Spotify playlist. The Flacco origin story always occupied an uncomfortable little niche which became even less comfortable as he became a quarterback in the crosshairs and I became a sports humorist required to have an itchy trigger finger.

I was there when the lights went out in New Orleans: Ravens 34, 49ers 31. The kid from calculus class, the terror of the Colonial Conference, the young man from the backyard fire pit was the Super Bowl MVP. Fireworks, I am told, hailed over little Audubon that night.

Flacco signed a $120-million albatross of a contract soon after the Super Bowl. His career immediately began listing sideways. He became, for several years, the standard bearer for both expensive quarterback mediocrity and the cringy “iS hE eLItE?” fad in sports discourse that was popular in the early 2010s. His name turned into shorthand for two different flavors of bulls**t — the winnersauce argument and the shrill overreaction to winnersauce arguments — both of which had also become my full-time stock in trade.

Even local fans here in Camden County appeared to turn on Flacco by the mid-2010s: not his classmates, certainly, but some of the older guys and smart-alecks around the bar. It’s hard to keep rooting for the hometown hero when he spends nearly a decade wearing an overpaid/overrated label. It’s easier to detach emotionally, pretend his success meant nothing to the community, pretend you never felt pride in his accomplishments. Joe Flacco? Big deal. My nephew intercepted him when Sterling beat Audubon in 2002.

Over the years, my connections to my former students faded. I took the gloves off when telling Flacco jokes, but I never stopped rooting for him to succeed, just as I root for the success of the doctors, teachers, principals, programmers, animators, writers, researchers, musicians, mechanics, electricians, cashiers and stay-at-home parents I once taught.

Flacco’s Comeback Player of the Year 2023 season felt personally validating. Flacco may once have been a Twitter meme, but his career outlived Twitter. Suddenly, folks in the local taverns remembered graduating with his sister, or were excited to report that they saw him picking up his kids from school. Snark and derision are fleeting, but perseverance, preparedness and professionalism are truly elite skills. Criticism is easy; survival is hard.

But of course, Flacco’s comeback is not a Ravens story.

Joe will play for the Colts this season, but his NFL career now feels complete. I am sure I will run into him at some town fair in the years to come. I hope to have the chance to sit and talk to him over a beer some day about parenthood, ping-pong and just about anything but the NFL.

3. Steve McNair

The Ravens traded a fourth-round pick to the Titans for McNair before the 2006 season. McNair was 33 and coming off a pair of disappointing seasons, but he had one last fine year in him. He ranked 10th in the NFL in DYAR in 2006, and the Ravens went 13-3 thanks to the league’s best defense.

Injuries and age caught up to McNair in 2007: he only played portions of six games yet fumbled eight times, retiring at the end of the year. We’ll encounter McNair again, in greater detail, when covering the Titans.

The Ravens traded for McNair because they were just a quarterback away from contention in the previous seasons. It’s time to talk about the quarterback who kept them away.

4. Kyle Boller

Last month, Boller concluded his pro day workout with the unconventional throw he mentioned to reporters at the combine. Boller went down on one knee at the 50-yard line and threw a sharp spiral through the uprights. (Since the goal post is in the end of the end zone, the throw was 60 yards).

Since that moment, the last thing on the minds of NFL scouts was Boller's college career. – Nunyo Demasio, Washington Post, April 23rd, 2003.

Cal went 3-8 with Boller at quarterback in 2000 and 1-10 in 2001. Head coach and soon-to-be-legendary quarterback guru Jeff Tedford arrived in 2002. He tinkered with Boller’s mechanics and upgraded the Cal offense. The Golden Bears went 7-5, and Boller threw 28 touchdown passes.

Boller did not participate in passing drills at the 2003 scouting combine, which was unusual at the time: every other major prospect (including Carson Palmer and Byron Leftwich) did. Boller did run a 4.6-second forty at 235 pounds, however, which furthered his rise up the draft boards.

Demasio quoted (sigh) Bill Polian, then the Colts president, in the article cited above. Heaven knows we cannot resist Polian spouting off like the Font of All NFL Wisdom yet again here in 2DZ:

He was not on anybody's preseason radar screen among [the media], the gurus, the [Mel] Kipers and people like that. They see the guy and say, 'Wow, Kyle Boller, we haven't heard about him.' Well, when you go talk to the personnel director or GM, he'll say, 'Oh, yeah, Kyle Boller is a great prospect.' But all those groups of people have heard all year is [Carson Palmer and [Byron] Leftwich." – Polian, via Nunya Demasio, the Washington Post.

Oh, those silly gurus!

The Ravens drafted Boller 19th overall. He won a starting job from Chris Redman in training camp. "Kyle has been very impressive," head coach Brian Billick said. "His physical skills are obvious, obvious to anyone who's ever even watched him practice. His ability to absorb the offense has been shocking to me.”

Boller was bad but not embarrassing as a rookie. The Ravens had a great Ray Lewis/Ed Reed defense, and Jamal Lewis rushed for 2,066 yards. Boller suffered a thigh injury after nine games, with Anthony Wright finishing the season.

Boller started for the entire 2004 season. He ranked 27th in DYAR, but the Ravens rushed for over 2,000 yards as a team, and they went 9-7 thanks to lots of 17-10 and 20-6 final scores. Boller was just young, athletic and non-embarrassing enough to earn benefit-of-the-doubt as a slowly-developing game-manager type.

Turf toe knocked Boller out of action on Opening Day in 2005. When he returned two months later, his interception rate returned to rookie levels. The highlights of his return were a 16-13 overtime win against the Steelers and a late-game comeback for a 16-15 victory against the Texans. Are you getting those Kenny Pickett goosebumps yet?

The Ravens traded for Steve McNair in 2006 and didn’t bother pretending that there would be any competition. Boller accepted his backup role and was called upon a few times to relieve the rickety McNair, leading the Ravens to a playoff-clinching victory over the Browns when McNair’s hand was stepped on by a defender.

"You can pout; you can be selfish," Boller said after that game, "But I've been raised and grown up to where that doesn't get you anywhere in life. I seized it as an opportunity to go out there and learn from this guy.”

McNair got hurt early in the 2007 season and was ineffective when he returned. Boller started for much of the year and took his traditional place as a bottom-quartile NFL starter. He suffered a concussion late in the season.

John Harbaugh replaced Billick after the 2007 season. Boller started the 2008 preseason opener but suffered a shoulder injury one week later, paving the way for Joe Flacco.

Billick has spoken often about what went wrong with Boller. Here’s one interview. The too long/didn’t watch: Boller was inaccurate.

Boller has become a poster child for the absurdity of the pre-draft process. The throw-from-the-knees is shorthand for some folks’ weird obsession with combine and pro day workouts; an obsession which, I think, peaked about six years ago and has recently ebbed.

Boller was bad, but I don’t think he was worse entering his third season than Pickett is right now or Mac Jones was ten months ago, and he handled his benching well. The Ravens thought enough of him to consider bringing him back as a backup in 2012.

It’s not Boller’s fault that he was over-drafted in a weak quarterback class. What was he supposed to do: not show scouts he could throw 60 yards from his knees?

5. Vinny Testaverde

Testaverde became the Ravens quarterback when the NFL used the Reality Stone to turn the Browns into the Ravens in 1996.

The Browns arrived in Baltimore in a sorry state. The beta version of Bill Belichick practically resented being forced to acknowledge the offense. Testaverde was a veteran caretaker who didn’t cower when the coach growled at him, so he was the team’s starter.

Ted Marchibroda replaced Belichick before the franchise retcon. Belichick acolytes Pepper Johnson and Carl Banks, who helped keep the Browns defense respectable, didn’t move with the team. The Ravens had the look and feel of an expansion team, right down to the two first-round picks that became Ray Lewis and Jonathan Ogden. Even with Lewis in the fold, the depleted 1996 Ravens defense was dreadful, forcing coordinator Marvin Lewis to shift from 4-3 to 3-4 fronts based on who was available.

Testaverde threw 33 touchdown passes and led the NFL in DYAR for the 5-11 Ravens in 1996. It was the best season of his career by far at that point. The switch from Belichick’s nondescript offensive coordinator Steve Crosby (who appears to have been Matt Patricia’s spiritual father) to the pass-oriented Marchibroda surely benefited Testaverde. The Ravens also found themselves in some shootouts, and Testaverde threw 19 interceptions, though his 3.5% interception rate was not unusually high for the era.

Testaverde reverted to form in 1997. Marchibroda, in the last year of his contract, tried to lure Jim Kelly out of retirement for 1998. Kelly declined. There was some confusion about whether Testaverde was even welcome at Ravens minicamp. Finally, the Ravens cut him at the start of June for cap purposes: June 1st cuts actually happened around June 1st back then.

As mentioned in the Jets edition of QB Top 5’s, Testaverde was either the best terrible quarterback or worst great quarterback in NFL history. I am leaning toward the latter, but we won’t know for sure until we talk about the Buccaneers.

Testaverde ranks below Kyle Boller because he had a reputation for fourth-quarter mistakes (five fourth-quarter interceptions in 1996, four in 1997) and because there were questions about his leadership in 1997.

6. Trent Dilfer

Dilfer led the Ravens to a 7-1 record down the stretch in 2000. He completed just 47.9% of his passes in the playoffs that year. But flags fly forever.

7. Tony Banks

The fumble factory who gave way to Dilfer in 2000. Let’s focus instead on my favorite Tony Banks: the keyboardist for Genesis.

8. Elvis Grbac

Grbac signed a five-year, $30-million contract with the Ravens in 2001, game-managed the team into the second round of the playoffs, got released in a 2002 cap move and promptly retired.

A Kirk Cousins-caliber quarterback would have led the Ravens to at least four Super Bowls in the early 2000s.

9. Anthony Wright

I don’t care anymore.

10. Jeff Blake

It was Blake or Jim Harbaugh for this spot. I kid you not.

Bonus Flacco Coverage

OK, one quick self-serving Flacco tale.

One day, in the downtime at the end of a rigorous calculus lesson, two of Joe’s teammates were drawing a play on the blackboard. It was the sort of spread-formation deviltry that Andy Reid might concoct to foil the Bills next January. It was new to the playbook, Audubon’s top receiver told me, and it was sure to lead to a win against whatever Camden County powerhouse the mighty Green Wave would face that Saturday.

I told the lad that the play looked nasty, but he had drawn it up incorrectly: unless Colonial Conference and NFL rules were different, there was a “covered up” ineligible receiver running a downfield route.

The lad looked at the board, then down at his binder, then back at the board. Joe was in the class too, and I like to remember him as quietly studying the diagram and analyzing the error. But it was his teammate who asked for a bathroom pass and ran to talk to Coach Ralph. (Why he did not ask for a pass to talk to coach, which I would obviously have granted under the circumstances, I have no idea.)

I ate lunch with Coach Ralph later that day. “Great catch on that illegal formation,” he told me. “We would have scored a touchdown on that play. And it would have been called back.”

And THAT’s the story of how I saved Joe Flacco from a Kadarius Toney situation. The moral of the story: if you want to make it as an Internet journalist, NEVER teach bell-to-bell.

If anyone is harboring any doubts about the way Black quarterbacks were treated in the not-so-old NFL, please consider Warren Moon.

6’3”, 220 lbs. Smart. Successful college career. Mostly a pocket guy, but with some mobility. Threw the prettiest ball in the game. He was basically Terry Bradshaw. If it wasn’t for that pesky pigment thing, he would be the most obvious #1 overall pick you could imagine.

But he went undrafted. Undrafted.

How powerful is prejudice that people whose jobs literally depend upon them winning football games can look at a quarterback like Moon and see only the color of his skin?

The only thing about Kaep that I want to mention is:

Lamar Jackson is like the refined, ultra-concentrated Kaep (yes he's a better passer too whatever) and it was really amusing when the league celebrated his 2nd best QB rushing day of all time without ever mentioning who #1 was...

despite #1 having done it with the same offensive coordinater and a head coach who is Jackson's head coach's brother.